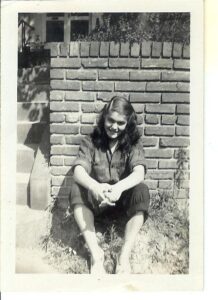

She wasn’t always just a sweet little old lady.

Don’t get me wrong; most of the time my mother, Lois C. Weaver, was a happy, loving woman. She was a nurturing mama, a doting grandmother, a proud great-grandmother. Indeed, her mothering instincts were always strong and kicked in at every opportunity.

Most of the time she was a perfect Southern lady, too; until her later years, Miss Lois never wore a pair of pants more than a handful of times a year, and then only because conditions called for it, like a deep snowfall, or going fishing. She even wore a skirt for most of a mother-son Scout camping trip when I was ten.

It was rare she didn’t wear a hat to church, although that style was going by the wayside before I turned her hair prematurely white being a precocious monster of a late-in-life boychild. But even after that boy’s hair was turning gray, Miss Lois still wore a hat to church.

She was a lovely hostess, a rock during crises (until after everyone else was cared for, and it was her turn to collapse) and a “cool mom” to my friends, as no boy, girl, dog, cat, bird, possum, worker or even a lost stranger left her house hungry except by their own choice.

She had a steel side, though. Although I was too little at the time to remember this specific instance, Mother let that armor show a few times, namely when a local grass widow about her own age started spending a little too much time, a little too close to the Old Man. Miss Lois didn’t paw and fawn and hang on Papa, nor did she cause a scene. She just carefully completely inserted herself into social situations and her dark brown eyes turned almost black as a warning. The grass widow got the message and moved on to pastures that weren’t as well-fenced. Papa was none the wiser; while Miss Lois never had to worry about him being unfaithful, she made dang sure, discreetly, that would-be harvesters knew that her field was well-tended, thank you very much.

Later in years she became the matron that so many knew, a fierce devotee of the arts and theatre (there’s a high school stage scholarship named in her honor back in what became our hometown.) She fought a thankless battle that many deemed futile for decades, saving an old house that is now a showplace, a museum and community arts center as its last resident had wanted. There were some who wanted to shift funds away from the community theatre and the arts center to other, more “worthy” projects, but they met the other Miss Lois, the stubborn one that didn’t quit.

She forged that stubbornness and honed it to a razor’s edge. Born on a rough farm in Northern Virginia, where my grandfather made ends meet by any number of side jobs, she tended her siblings and gathered eggs and helped Grandmother with the house and worked the fields and even helped fight a wildfire when all the family had was buckets, feed bags and a pitcher pump. She learned to fight and play ball and roughhouse with her brothers; a ball game with them left one of her knuckles shoved back into her hand, and with no real medical care available, it healed that way.

After the family lost the farm and moved to Washington, D.C., she carried a hat pin to defend herself against ne’er-do-wells, where it wasn’t safe for an attractive young woman with nice curves and pretty legs to walk back and forth to work at a doughnut shop. Later, when she found herself a divorced mom with four children, she worked multiple jobs and was still a mother. One of those jobs was how she met my Old Man, whom she called the meanest editor ever, but admitted he gave her a chance and taught her to write something other than the ”women’s news,” which she passionately hated.

Women’s news, as it was called then, was comprised of weddings and births and social news. Miss Lois wasn’t made for that; she earned a reputation as a crime reporter, then a court reporter, as well as someone who could pull the soul out of a feature story and share it with the reader. (Another writer and editor paid Mama that compliment, and she nearly cried.)

But her words weren’t just about murders and crimes and council meetings and interesting people and flowers; she wrote dozens if not hundreds of poems. She dabbled in painting and drawing. She could look at the simplest and strangest things and find art in them that was whimsical and appealing to everyone, like her famous gourd snake Hissy Lissy, and the Trashcan Angel I write about every Christmas.

She could doctor a little kid’s injuries in the simplest ways, and they would heal. Hot tea, real chicken soup, vinegar, comfrey leaf poultices and strips torn from old sheets could and often did heal almost anything, especially when applied with a gentle, loving hand and some kind words (or sometimes, a stinging admonition to remind a little boy that if he’d have listened to his mama, he wouldn’t have needed some homegrown medical care.)

In those times when a mother’s medical skillset wasn’t enough, she could be counted on to call down a nurse or doctor who wasn’t treating a situation with the urgency she felt it required. She was never what we now call a Karen, but she didn’t quit, either. As my father’s health deteriorated, she was a ferocious advocate, a hero to some nurses for being willing to stand up for her kin – and a polite, insistent pain to many doctors and specialists.

She would devote sleepless nights to around-the-clock care for any orphaned animal that made it to her doorstep. If the animal survived, she would cry when it was released, and she would cry if it didn’t make it.

I hold my mother responsible for my willingness to judiciously pick up hitchhikers. Papa was away on business once, and I was a proud 12 year old man of the house. I ran a fellow off who was looking for a meal, and made the mistake of bragging to my mother how I had done so.

I had to run the guy down, apologize, bring him home, help serve him lunch, and give him the last of the homemade pound cake for dessert. There was enough that he could have something to eat for the rest of his journey.

Desegregation quickly and fundamentally changed schools when I was a child, but not the hearts and minds of some folks. Miss Lois was no crusader, but my black friends ate at the table with us, slept in our house, and were treated the same as my white friends. The same went for Latinos; more than 35 years later, people still remember how Miss Lois was covering a murder trial and ended up sitting in the courthouse hall, holding a Mexican baby, comforting the baby’s frightened mom and other kids, while wrangling a court official who would find an interpreter. Ironically the interpreter who showed up was from the same province of Mexico as the woman and her family. I must note that Miss Lois didn’t speak Spanish, but she spoke babies, love and human decency.

As her health went down, and the demon that is dementia took her from us, she fought to hold on to those things she held dear. She would cry in frustration when she could no longer sew, and her crocheting became a tangled mess. In a way, the loss of her mind was mercifully fast, but when she was still aware, there were a few times she found out that she had done something out of character, and she was mortified. Sometimes she laughed about her misadventures, but usually they hurt and embarrassed her deep inside.

Toward the end, when she didn’t recognize anyone and could barely speak, her doctor (one of the best) convinced us we had done all we could, and we were not breaking our promise that she would never have to go “into a home” other than her own. She didn’t last long after that, really just a few weeks, before her final stay at the hospital. She smiled and laughed a lot before then, as God mercifully put her mind in a happy place while her body betrayed her in front of her children.

She fought to the very end; on her last day, her eyes had that angry, determined look while she was fighting for her last breaths, and her hands were clenched, fighting as she had fought the wildfire, fighting as she had to care for her children, fighting as she had to make a home and love my father and save an old house and teach her children right from wrong and save a baby squirrel.

The Valentine’s Day when she died was cold, rainy and icy; a single bird perched precariously on a tree limb outside her hospital room. I remember thinking how Miss Lois would have wanted to bring it inside, warm it up, give it something to eat, then maybe write a poem about it, or sketch its picture to convert to a needlepoint.

She almost smiled when she relaxed and went home; naturally she went to Heaven on Valentine’s Day, since she and Papa always had some kind of date on Feb. 14, whether it was just coffee, dinner or a play in the theatre she so loved.

She wasn’t always the sweet old lady so many folks knew and loved; she was also a wife, an artist, an advocate, a teacher and when necessary, a warrior.

Lois Weaver was also the best mother a man could ever have, and even more than 20 years later, I still miss her every single day.