The things I take for granted are things they never knew.

I am writing these words in a comfortable, air conditioned office, despite the thermometer soaring to sinful levels. I had a good supper last night with my wife, plenty of coffee this morning, and I have a choice of lunch. I’ll most likely sleep in a comfortable bed tonight, safe in my home.

It’s hard for us to have a perspective of those who went before us when we think about Independence Day, when we commemorate the signing of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776.

It can be even harder when we think about the events leading up to July 4, 1863.

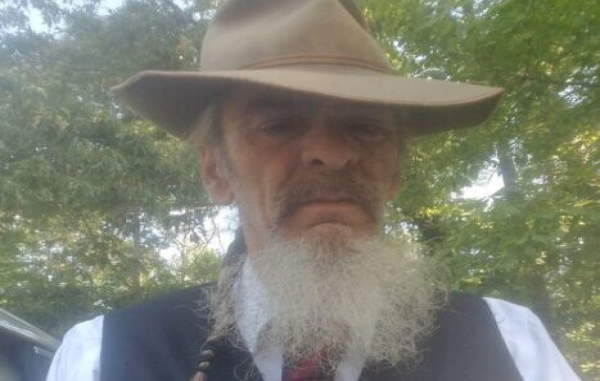

A desire to understand my ancestors was one reason I was once a reenactor, a living historian as we preferred to be called. After a couple years in the hobby, I drifted more and more toward the “hard core,” authentic side of reenacting. I found folks who had more of the same deep desire to understand everything about our ancestors, whether they fought for the North or the South. I had folks on both sides, by the way, although most were Southrons, a quaint, forgotten word now often looked upon with disdain. Since my focus was the history, not the histrionics, I wore both blue and gray during my time in “the hobby.”

Near as I can tell, none of my family owned slaves at the outset of the War Between the States. While several had owned their fellow men before the war, most never had, but times were already changing. A couple had former slaves employed in their households, farms or in one case, a metalworking firm. One steadfastly sat on a chest of silver dinnerware when the family home in Petersburg was entered by federal soldiers. She refused to move, and for decades bragged and laughed about standing down the Yankee army. As a child, my father was cared for by her granddaughter, who was born free. Even after receiving their freedom, their family stayed on with my father’s family, but as paid employees.

I am not, under any circumstances, defending ownership of other people. It’s horrifying to me. At the same time, it’s horrifying to judge folks long dead by the standards we now consider right.

My kinsmen who fought for the Confederacy and left a written record didn’t fight for slavery; they fought for the freedom from what they saw as an ever-more intrusive, corrupt government. I don’t know about the ones who didn’t leave a record. At least one, maybe a couple of them likely couldn’t read or write. Again, something we take for granted, the ability to read and write, was something that they never knew.

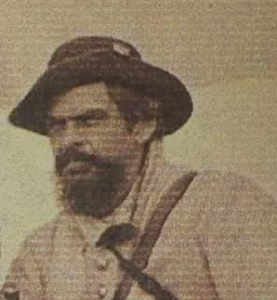

As a child I knew of the Battle of Gettysburg only through books, and stories retold by my father, stories he heard at the knee of his grandfather and his great-uncle, my great-great-uncle, Capt. Tom Traylor. Later, I was able to get hold of some precious letters, newspaper articles and diary pages written by Captain Traylor.

He referred to the best-known battle of Gettysburg, the field at Pickett’s Charge, as the “Field of Pain and Sorrow.”

The desire to see and feel something that Captain Tom and some of the others may have known was one reason I made extra efforts to make it to Gettysburg that year. Four of us rode up in a friend’s van, driving through the night and camping out in a grass parking lot in the town of Fairfield, next door to Gettysburg. When we awoke in the morning, we discovered we were almost under a local historical marker describing how the vacant lot had been the site of a Confederate hospital after the battle, and the dead were lined up for burial about where we lay.

Later, we went to the National Battlefield Park; stoked with a good breakfast, we were well-hydrated, and motivated. We were going to cross the field where Pickett’s Charge had taken place, despite the fact that the field was overgrown. We couldn’t carry our muskets, of course, but otherwise we were equipped and dressed as had been the men who destroyed a crop and made Gettysburg famous back in ‘63.

We weren’t far into the high grass when we realized we had made a mistake. Our canteens were banging empty on our hips before we were halfway through the thick grass. The creek at the bottom of the field threatened to tear off our handmade brogan shoes, and it left our high-end reproduction wool socks slippery, slimy and soaking wet.

We weren’t being shot at, of course, the battlefield being a much more peaceful place today, but the effort took its toll on all of us. Walking a mile on a sidewalk or even a dirt trail is nothing compared to a mile through head-high grass with invisible pockets of water, on a day when the temperature has already touched 93 at 10 a.m. and you’re wearing a fabric made of cotton and wool, with a blanket roll, cartridge box, bayonet, canteen and haversack slung from your hips and shoulders. Even without a ten-pound musket and six pounds of live ammunition, our soft lives shone through as we gasped and staggered along. I wondered if any of those who passed before us also gratefully gulped handfuls of water from the creek or soaked their neck rags before continuing toward the split rail and stone fence across the road.

Our goal was the North Carolina monument, where troops from our state earned the moniker “Farthest at Gettysburg.” We got separated, but we broke through the tall grass at about the same time, stumbling into a mowed portion of the field, even though we were far apart. Our air conditioned ride was waiting nearby.

I turned out to be the closest to the marker, and my steel heel plates tapped dull on the hot soft pavement laid long after the noise of the regular world replaced the shots, screams, payers and curses of the men who died there.

The marker wasn’t as impressive as so many others on the field. I was a little disappointed, I guess. I stood for a moment looking at the simple monument, something that wouldn’t have been out of place on a property line, or in a family cemetery.

Then a bus load of tourists began yelling, cheering and clapping, wanting me to turn their way for photos. They were cool, happy, and having the time of their lives. Apparently seeing three Confederate soldiers emerge from the overgrown field like ghosts was the high point of their lives.

It angered me.

I stood there with tears in my eyes, scratched and bloody from the grass, my pants muddy, my shoes sopping wet, clothing soaked in sweat, thinking of those who had cross that field before, under other circumstances. They, too, got separated from their friends, but my friends were waiting for our comfortable van with a cooler of water and Gatorade. Some of those men never saw their friends again, unless they were on a burial detail.

These people were smiling, laughing.

They didn’t understand the sacrifices on both sides of that fence. Truth be told, I couldn’t, either, but I was able to enjoy the freedom that ironically, both sides fought for. It broke my heart to think of these men, some of them a decade and more younger than I was on that hot day, standing and dying beside their friends and family in a battle line, shoulders sore from recoil, eyes smarting from smoke, teeth blackened from tearing open paper cartridges that were then shoved down the muzzle of a rifled musket and fired with a percussion cap placed on the cone by fingers scarred from thousands of previous thin copper caps.

They were men who would never see their families again, never feel the warm earth turned by a plow, never again know the kisses of their wives and children, the feel of a horse between their legs, the bay of a coonhound on a crisp night, the camaraderie of friends in a tavern, or the joy of worshipping in a church on a Sunday morning.

I looked back across the field, and thought for a moment how so many men died or were ruined, and how our country, the greatest country ever made, was almost riven in two.

Then I understood, as best as any of can, why my great uncle Captain Traylor called it a Field of Pain and Sorrow.