North Carolina has dodged Chronic Wasting Disease in its deer population for years, and state officials hope it stays that way.

The Wildlife Resources Commission is increasing monitoring efforts for chronic wasting disease(CWD) this deer season. Over the summer, Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources reported that a deer harvested just over 30 miles from the North Carolina border tested positive for CWD. It’s the closest case reported to date and prompted North Carolina wildlife officials to escalate surveillance measures already in place, as well as introduce new monitoring initiatives.

The disease is spread between deer through direct contact and environmental contamination from infected saliva, urine and feces of live deer or carcasses and body parts. CWD is caused by abnormal proteins, called prions, that slowly spread through a deer’s nervous system, eventually causing spongy holes in the brain that lead to death. There is no vaccine, treatment or cure. Deer do not recover from CWD and the disease is always fatal.

To date, CWD prions have not been documented to cause sickness in humans, but closely related prion diseases, like bovine spongiform encephalitis – also known as mad cow disease — have made the jump. The CDC does not recommend the consumption of CWD-infected meat.

The Wildlife Commission has been monitoring for CWD since 1999 through coordinated statewide surveillance. Samples from over 15,000 white-tailed deer have been tested, and to date, CWD has not been detected in North Carolina’s deer herd.

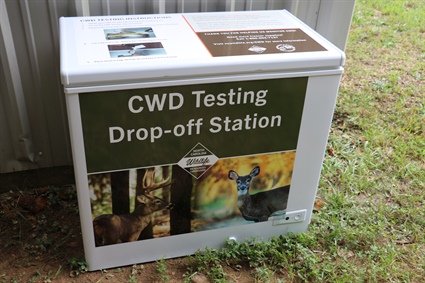

There is no reliable USDA approved live test for CWD, so effective surveillance methods require the testing of dead deer, primarily hunter harvests. The Wildlife Commission is making it easier than ever for hunters to help surveillance efforts by setting up more check stations around the state and installing drop-off stations where hunters can voluntarily submit their deer heads for testing.

“We are fortunate that we haven’t detected CWD in North Carolina, but the best way to monitor for the disease is with continued testing, relying heavily on hunter cooperation,” said Moriah Boggess, deer biologist for the Wildlife Commission. “The self-serve sample drop-off stations we’ve installed in each region of the state will allow us to collect as many deer heads as hunters are willing to donate.”

The agency’s CWD webpage, ncwildlife.org/CWD, features an interactive map of the drop-off station locations and allows hunters to view their deer’s test results.

Testing is important because it’s hard to tell if a deer has CWD. Signs of illness aren’t visible for at least 16 months after infection. The slow incubation period and the ease of transmission is why wildlife biologists say being proactive and following current regulations is imperative.

Deer hunters can expect:

- Additional voluntary check stations in targeted regional zones.

- New voluntary testing drop-off stations statewide.

- Increased efforts to test deer from vehicle kills, taxidermists and meat processers.

- Continued enforcement of importation laws.

Importation of whole carcasses of cervids (deer, elk, moose or reindeer/caribou) from any state, Canadian province or foreign country is prohibited. If you are transporting cervid carcass parts into North Carolina, you must follow processing and packaging regulations, and carcass parts or containers of cervid meat or carcass parts must be labeled and identified.

Other states already dealing with CWD have experienced a decline in their deer populations where the disease is most prevalent, a decrease in mature bucks and some hunters have become wary of eating harvested meat. It’s changed the deer hunting culture and tradition, which Wildlife Commission officials want to avoid in North Carolina.

“Deer hunting is important to North Carolinians’ heritage and food systems. We are ready to manage CWD if it’s detected, but we’re doing everything we can to keep it out,” said Boggess.

The Wildlife Commission recently adopted a comprehensive Chronic Wasting Disease Response Plan that will be activated immediately if CWD is detected within the state. The response plan was developed by wildlife biologists with input from other state wildlife agencies and in cooperation with the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (NCDA&CS), which manages farmed cervids. Although the NCDA&CS also has a plan specific to their oversight, the two agencies work collaboratively.

For more information about CWD, visit ncwildlife.org/CWD.