At least two of my ancestors were truly insane.

We don’t like that term nowadays, of course, but even 100 years ago it was commonly applied to people who had serious mental illness.

One of my kinsmen went over the edge after he found the remains of his slaughtered wife and all but one child scalped during the French and Indian War. He was an educated man, a teacher turned farmer in colonial Virginia, a refined man who could quote Shakespeare, fluent in Latin and Greek. He became one of those vengeance-seeking colonial warriors who dressed in Indian garb and waged a private war, alongside a number of other guerillas. I do not have space to share all the stories about him, but he had problems dealing with the end of the Seven Years War, as that conflict is often called. A few years later, he went on to serve in the American Revolution, earning a letter of commendation from George Washington himself.

I have no idea if he ever got to read that letter, since by the time the Revolution was over, my kinsman was chained in the attic of his surviving son’s home. He was prone to attacking folks he thought might be Native Americans threatening his family.

Another relative went “mad with grief,” as the newspaper account put it, when he discovered his pregnant wife had fallen through their porch while he was out of town. He had put off fixing the porch, and rode back into town just in time for the funeral. A stranger told him what had happened.

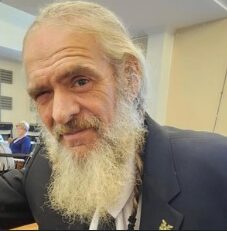

He tore off most of his clothes, screaming when he saw the coffin, and ran away. He lived for months in the woods around his hometown, occasionally stealing a chicken, raiding gardens, eating raw meat and rooting through garbage for food. His exploits made for popular stories in the newspapers of the time. His hair and beard were long and unkempt, his fingernails broken and dirty, and he jabbered at the men who finally tracked him down and caught him.

He became an early resident of the Staunton State Hospital in Virginia.

Mental health care has always been a tricky, distasteful subject. We know now that the almost medieval torture techniques used into the early 20th century were as horrible as they were ineffective. I hope that no modern person can conceive of paying admission to “Watch the lunatics,” as was once a common practice. Indeed, were a doctor to write a novel titled “I Knew 10,000 Lunatics” today he might be brought up on charges, yet the late Dr. Victor Small’s novel based on his years at Dorothea Dix Hospital sold thousands of copies in its day.

Times change, treatments change, definitions change, but people don’t change. Some still get sick in ways that can’t really be helped with medication or therapy.

When you throw in the effects of fetal alcohol and drug use along with everything else, I think sometimes we have even more folks in need of help than when my five-time-great uncle was kept on a chain on the grounds of Staunton so folks could see the “Wild-Man”.

It was natural that institutions for the mentally ill would fall out of favor, based on the advances in medicine and more understanding of the causes of mental illness, as well as the systemic abuse of patients in asylums through eugenics and drug tests. Then there were the teens and young people who were locked away simply because they didn’t agree with their parents’ values. Mental hospitals and mental health care became symbolic of horrible abuse in the 1950s and 60s.

Deinstitutionalization began to be talked about in the 1960s, but it took 40 years to come to fruition in North Carolina.

In the early 2000s, I had the opportunity to tell a state senator and others that I had reservations about the state’s plans to radically change the mental health system. We have dealt with mental illness in my family (in modern times, for reasons other than the trauma suffered by my ancestors). I have dealt with it in my police reports.

Heck, back then I dealt with it at my favorite restaurant, since one of the regulars was a fellow who had been booted out of a shutdown state hospital. He was friendly and fun most of the time, but those who knew him came to recognize when he was having a dark spell. He’d be taken away for a while, gotten back on his medications, and then sent home. He usually got a smiley face sticker on his coat or shirt when he was released, and he liked showing it to people.

The drug epidemic has given rise to a massive new industry of “mental health care,” but the problem is that drug addiction is not the same as a mental illness. However, there’s significantly more “free” money for treating addiction than there is for mental illness, and with no disrespect intended toward those in that field, it’s easier to deal with an addict than a screaming man who is convinced the spider-people are coming to get him.

Some dear friends of mine are facing a heartrending decision; they have a special needs child, who due to several circumstances simply cannot get the help he needs in their area. They might have to have him placed in one of the few remaining hospitals that can provide the care he needs, and that’s hours away. They love him as only parents can, and the only available options are tearing them apart.

I knew of an elderly lady who dedicated her life to caring for her grown son, a big strapping fellow who never developed the mental acuity of the average teenager. For years she was the only one who could “handle” him, but as he grew bigger and stronger and she got older, he would sometimes injure her when he got upset. He was never able to care for himself, and when she died, things just got worse. I cannot imagine the terror that poor fellow felt and could not express in ways that anyone could understand when he was chased down and handcuffed by police who honestly didn’t want to hurt him.

There are some folks with mental issues who are perfectly capable of functioning in society. Some have good familial networks of support. Others have just learned how to deal with their issues, who to call for help and how to reach out when they feel bad things happening. Some try to self-medicate with illegal or prescription drugs, thus compounding the problems.

But there are others who are alone and simply cannot be handled with medication, routine, therapy and a structured homelife. They need institutions where highly-trained professionals can deal with the spider-people.

There are signs that, as one commentator said, the pendulum may be swinging back toward state hospitals for the mentally ill. I hope this to be the case. Without seeming to diminish the evils of addiction, I hope that the mentally ill get the respect and care they deserve. There’s a well-defined line between true mental health patients and addicts who adopt the moniker of mental illness to avoid jail time. The two problems are not intertwined, and when they are lumped together, the mentally ill get the short end of the stick.

I hope the bureaucrats and profiteers who are already printing hundred-dollar-bills in “addiction treatment” can be prevented from getting their claws into whatever money our state does decide to put into real mental health care. There’s a need for residential drug treatment facilities, without a doubt – but there’s a need to care for those who did not choose mental illness, too.

It gets said all the time that we cannot prosecute and incarcerate our way out of drug addiction.

I say that we cannot treat mental illness with just a smiley face sticker, a pill and a pat on the back for someone to be turned back out on the street on their own to face the spider-people.