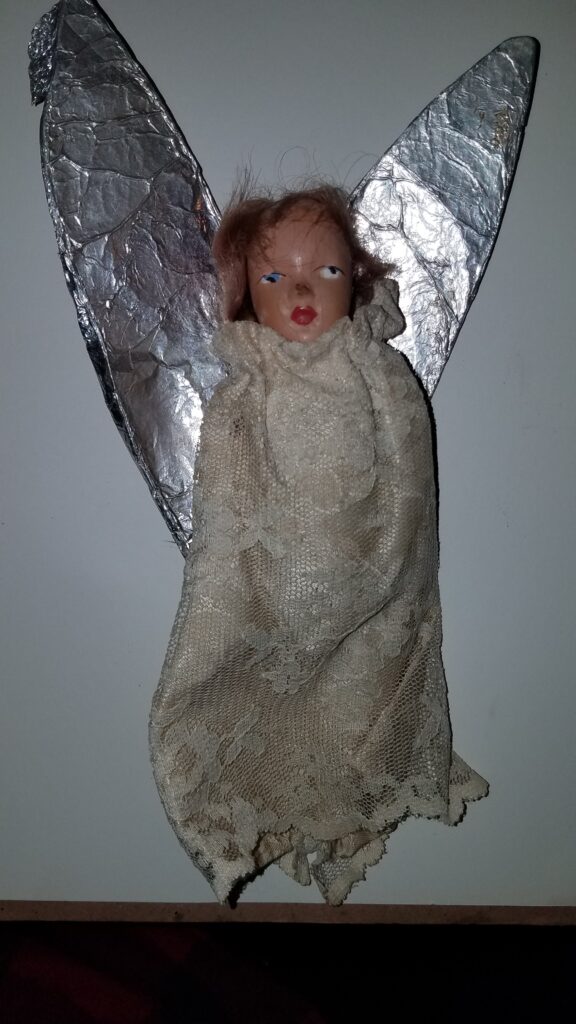

More than a century ago, maybe even on a Christmas morning, the doll was unwrapped to squeals of joy.

Her body was simple and straight forward – basically just cotton bags, stuffed with more cotton. She was made in the Victorian era, so unnecessary curves were not allowed. She was cut from a pattern, then the seams stitched together, shaping the arms and legs. Then the legss were sewn to the body, and a collar made to hold the porcelain head on place. The porcelain arms with their tiny hands were attached much the same way. Her hair was glued in place, and her eyes and mouth painted by hand.

We have no way of knowing whether she was sold through one of the stores in the little beach town on the river, ordered through a newspaper or catalog, or purchased on a trip to Washington City, Richmond or Fredricksburg. We don’t know if she sat in as store window until one day when a doting father or a loving mother saw her, or if a little girl saw her on a shelf and was utterly, completely lost.

She was probably dressed in the same doll-finery beloved by little girls of all ages, everywhere. It’s entirely possible, given the era of her origins, that her little girl’s mother made matching outfits for the daughter and the doll.

I can imagine the little girl playing behind the fancy wrought iron fence that faced the river when I was a little kid. I don’t know for sure which house the girl lived in – that was a good fifty years or more before any of my mom’s family lived at Colonial Beach — but somehow when Mother told the story, I thought Miss Lois might have found the doll behind one particular house with its view of the river and the boat harbor downstream, a bit removed from the big old hotel and boardwalk a few blocks up.

Those houses were built after the War Between the States, when there was money being made and the land was healing, when the country was growing. People began coming from Washington and elsewhere to spend their summers at Colonial Beach. Local tradition held that Alexander Graham Bell tinkered with plans for his newfangled contraption called a telephone during an extended visit at one of those homes.

Regardless as to whether Dr. Bell ever spent any time there, it wasn’t hard to imagine little kids playing on groomed green yards just a few dozen steps from the Potomac. It wouldn’t be a stretch to see the little girl who owned the doll making her way down the street with her parents, the doll in a miniature baby carriage, wheels rattling against the wooden sidewalk that kept folks out of the oystershell streets.

The doll was a product of a happy time, and likely was mute witness to many more, even happier times. It wouldn’t surprise me if she was eventually handed down to another little girl, a daughter or good friend who was worthy.

But somewhere along the line, the world changed.

The town grew, but the old homes were not as impressive as they had been. Then came the Depression, and hard, scary times for everyone. Some of the old houses were rented, some bought by other folks for a primary home, one or two became less-than-reputable boarding houses, and some were just shuttered and allowed to decay.

The town came back, and in the boom times after World War II, it was once again a busy place in the summer. But most of the old houses were just sad, old houses.

Somewhere along the line, the doll had been left behind.

Maybe the last little girl to own the doll simply lost her porcelain friend, and cried her eyes out for days. Perhaps she outgrew such silly things. It’s entirely possible the doll’s last outfit was desperately needed to patch a worn garment so someone would appear presentable for a badly-needed job.

Whatever the reason, she ended up forgotten and unclothed, somewhere that the mice occasionally nibbled on her. Her legs disappeared, and the china in her face and arms cracked and faded.

One cold dreary day with a hint of snow in the air, when the big chunks of ice were forming on the Potomac and the last of the waterfowl honked their way mournfully south, the naked doll was thrown on top of a trash can and placed in the alley behind one of the old houses. Some workers were cleaning the house out, and the doll joined all the other forgotten garbage to be hauled away.

A woman lived in that town then, a stubborn woman with four kids. She worked two retail jobs and was trying to learn how to write for a newspaper. She worked at the grocery store, the department store and the newspaper, then took in sewing as well. She and her children didn’t live like the folks who originally lived in the old houses on the waterfront, but they were warm and fed, and had a home with her mother, just a few blocks from the boardwalk and the beach.

She cut down the alley, cold wind cutting through the heavy socks she wore over her stockings, her skirt a little damp from the rain and the first snowflakes. The alley was a short cut to the department store, and the houses gave a little relief from the wind roaring off the Potomac.

She was worried about Christmas; she had a sneaking suspicion that her editor, a skinny, sad, lonely man who lived up the river with a beagle named Driver, had bought presents for her and the children. She wanted to do something nice for him, and her mother had invited him to dinner with the family. She also wanted to do more for her children, her mother and her sister, but money was tight. She had already decided she was going to make an applesauce cake for the editor, but she wanted to get a few more things, too.

Then she saw the doll.

It lay there embarrassed in the trashcan, mousechewed and naked and alone.

The strong, stubborn woman had a soft streak, too., She snatched the doll from the trashcan, and shoved it in her pocketbook. She didn’t want people to think she was rooting through trashcans in the freezing rain.

When she got to the department store, she used some of her next week’s lunch money to buy some lace, gold embroidery floss, and tiny pearl buttons.

That night, she used an old piece of silk to make a dress for the angel, and overlaid it with the lace. The floss became a tiny halo. Tinfoil and cardboard made wings. More of the floss made a loop for the back of the angel’s robe to attach to the tree.

She made the cake for the editor; in fact, she baked one for him every year after they were married. She bought extra presents for her mother and sister and children, using the extra hours she earned at the store.

But the doll that became an angel was a gift to herself.

Every year, as we fought with and fiddled at and finally finished the tree, one thing remained the same. Mother’s Christmas tree was complete when she hung the angel. It was misplaced the first year after Miss Lois died, but just when all hope was lost, Miss Rhonda found the angel. When our home flooded, and we balanced flashlights whilst wading in brown water and deciding what we could lose, Miss Rhonda made sure the angel was kept safe.

My sisters bug me every year to send them the angel – after all, I wasn’t even born when our Mother saved the angel from the trashcan. There was at least one more applesauce cake before the sad, skinny editor could be happy again, when he married my mother.

But I can’t quite let it go. Next year, maybe, I always tell myself. Becky and Sharron tend to overwhelm everyone with Christmas – and I’m happy that makes them happy – but I always worry the angel will be lost in all the bright lights and baubles and Santa Clauses.

Instead, the angel gets to hang on the single little tree that graces our house, often a “Charlie Brown” tree rescued from the firepile at a tree lot, or a sapling that wouldn’t have lasted beyond the next mower pass on the power line right of way.

There are bits and pieces brought by both of our families on the tree, just as the angel brings bits and pieces of other families whose names we don’t even know, people whose happiness the angel shared decades before a strong stubborn woman named Lois decided she would marry a sad, skinny man named Tom, and they decided to be happy together.

Every time I see that old doll Miss Lois saved, I am reminded of how Christmas is about the birth of Jesus. Not just the obvious parts about the angels, but how he was born for me, and you, and everyone else, despite the sinful choices we as humans make.

God looked down on us, and didn’t see us as something to be discarded. Instead, he saw something worthwhile. He sees what we could be, not what we were or even are.

He saw us in much the same way that a mother can look at a broken, lost doll, and see instead the angel in a trashcan.