For weeks, it seems the country has been devoted to the tragic story of a lovely young woman named Gabby Petito.

Videos and photographs show a happy, spirited young lady trekking across country with her fiancé. Then there’s another video, where she is crying and taking the blame for the fiancé’s actions. Her body was later found in a campground, and you know the rest of the story.

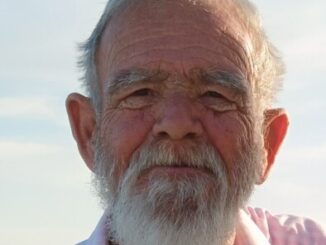

She was a couple years younger than a little boy that I never met, yet who would become such a big part of my life, and the lives of a lot of other people, on a clear October night in the year 2000.

Tristan Buddy Myers would be 25 now; he likely would have already had a cross-country trip or two, since his great-uncle drove a big rig, and Buddy loved the tractor trailer. He might have been a ballplayer, a soldier, a teacher, a preacher or yes, even a truck driver.

Things were looking up for Buddy on the day he disappeared from the modest home on Microwave Tower Road near Roseboro. He was a happy little boy with two dogs and a good home and a family who loved him. He loved his neighbors’ horses. He had his own bed, and good food.

It was a far cry from where he came from, which we won’t worry about right now. Suffice to say, before John and Donna took in their great-nephew, he couldn’t get a break, which is bad when you’re four years old.

My editor called after we had gone to bed, and he sent us scrambling to where firefighters and deputies and volunteers were searching for a little boy. Flashlights cut through the dust kicked up by the vehicles on Microwave Tower Road. People were calling “Bobby! Bobby!” because they had misheard his name.

I will never forget the image of lights crisscrossing and voices calling in the night.

For three days, we searched. I say we, even though I was a reporter, because I searched, too. I walked some of the trails. I helped strangers find intersections of hunting trails and farm roads on maps, strangers from a dozen states who volunteered to come help find a little boy. I wrote my stories, of course, and directed a photographer, but Buddy became everyone’s child for three days, and everyone wanted to find him.

The town of Roseboro grew by about 40 percent during that search— it wasn’t a big town, and still isn’t, but literally hundreds of people came to help. They brought food and gasoline and batteries. There were black folks, white folks, Indians from Robeson County and Cherokee, Yankees, and Southerners. There were hardcore, professional searchers, and men and women with four-wheelers and an intimate knowledge of every deer trail for miles around. For three days, they took time off work and preparing for hunting season, focusing on finding a little boy few of them knew.

All anyone ever found were a few footprints and a toy dinosaur that Buddy carried with him all the time.

I’ve covered other searches where less was found, as well as searches that had happy endings, with living but lost people safely rescued. I’ve been on others where the best anyone could say was that the family got closure.

But with Buddy, there was no closure. There was no happy or sad ending. There is no ending, because he is still missing.

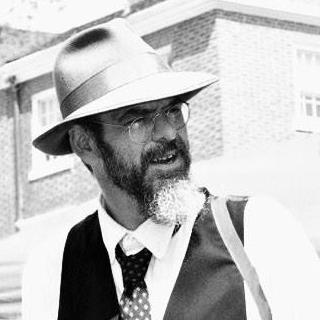

I made a friend during those days, a friend I still treasure, one of the most incredible women I have ever met. Monica Caison of the CUE Center was one step away from poking her finger in the chest of the chief deputy (who was also a lifelong a friend). The chief was always a steady hand, and this day was no exception. He didn’t take the haranguing personally.

As I got to know Monica through the years, I understood better why she was sometimes so doggone aggressive. The missing haunt her dreams every night. I couldn’t do what she does, but somehow, she still fights for the missing and their families, even to this day.

For years afterward, Monica deals with those who are startled by the ringing telephone, who hold their breath when a car pulls in the driveway, hoping, praying, begging that there will be some news. Everyone hopes for a miracle, of course, but many just want to know something.

Most never will.

I had a troubling few minutes the other day before they found Gabby’s body. The news showed yellow ribbons on utility poles, houses, mailboxes and everywhere anyone could tie one. There were yellow ribbons everywhere in Roseboro 21 years ago, too. They hung on for years, stubborn and faded, like the memory of a little boy who wandered away and never came home.

If nothing else good comes of it, the disappearance of Gabby Petito helped remind people of the hundreds of people who go missing every year. It’s very easy in the news business to disregard some missing reports as runaways, drug addicts, or even people who have just had it and never want to see their families again. Readers get tired of seeing more stories about the same missing person. We’re human. It happens.

Indeed, I was once told by an editor that there was no reason to run a column about Buddy, because nothing ever changed. It was still the same, and he doubted that many people cared anymore. I reckon some don’t, and that’s a shame.

You see, Monica taught me something very important in those days looking for Buddy.

Every missing person is somebody’s child.

For a few days in October 2000, Buddy Myers was everybody’s child.

The yellow ribbons that hung for Buddy are long gone now, occasionally replaced by others which have also faded and frayed.

But for some of us, those ribbons will never be forgotten. We remember that every missing person will always be somebody’s child.