The weather front came in the night, dropping temperatures thirty degrees in a matter of hours, announcing the onset of real fall weather with a curtain of blowing, cold rain.

It was the type of weather that made the deer move, set the ducks to flying, put the coons in a foul mood, and caused the hounds to jump and sing in anticipation.

For most of us, it was a weather change we always wait for, that first cool blast announcing October’s premiere as September fades into a golden sunset.

But on that particular day it meant the loss of hope.

When Buddy Myers slipped out the front door of his home on Oct. 5, 2020, it was a beautiful day. The leaves were changing, the corn and tobacco were long since down, and soybeans were weeks away from harvest. High school football, which was nearly a religion in Sampson County, was in full swing.

Hunting season – which for most folks meant deer, although small game and coons were on some agendas – was days away. Summer wasn’t a complete memory, since there were still mosquitoes the size of small birds, but it wasn’t long before a good killin’ frost would destroy the mosquitoes, harden the pumpkins and ripen the persimmons.

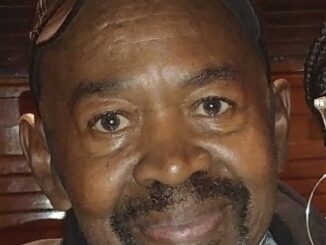

It was a lovely day, but Buddy and his great-Aunt Donna were tired. Of course, a four-year-old boy like Buddy with two dogs will exhaust anyone. They laid down in the living room to take a nap, and Buddy disappeared.

Donna and her husband John opened their home to Buddy when his grandmother got sick; she was raising the child because Buddy’s mom Raven was an unwed young mother who made some really bad choices. At the age when most folks are enjoying grandchildren, John and Donna found themselves being parents again, and they loved it.

Living with Donna and John, Buddy could just be a little kid. I got to know them over the next couple weeks and years, and though I never met him, I could tell that child was in Heaven. Donna and John doted on him. He had two dogs and lots of toys. He had a stable, clean, loving home like every child deserves. He had good food and the medical care he needed. John drove over-the-road trucks, and like most little boys, Buddy loved the big rigs. He could visit the neighbor’s horses, just a short distance from the house, but still where Donna could see him. You can see his happiness, his comfort, in the pictures. He was a little boy like any other child, loved and probably spoiled a little.

But on Oct. 5, 2000, Buddy managed to slip past a door alarm and disappear with his two dogs.

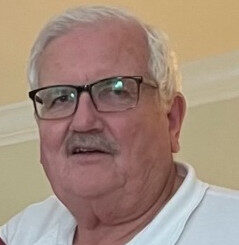

Investigators estimated that Buddy vanished around 4 p.m. The Old Man and I were working on routine stories; Miss Lois had filed one earlier that day. Miss Rhonda was at the radio station, where she was every day from noon until 9.

Around 11 p.m., moments after we had all gone to bed, the phone rang. My editor wanted us on Microwave Tower Road, Roseboro. A little kid was missing.

Microwave Tower wasn’t paved back then, so clouds of dust cut by headlights rose above the trees. As we joined the speeding, anonymous caravan of vehicles heading up the hill to John and Donna’s, you could hear people shouting “Bobby! Bobby!” They didn’t have his name right, but that would change.

Rhonda and I rode with two Wildlife officers to check the horse paddock. We rode down a rutted, broken red clay and sand road, shining flashlights into the woods.

I made the last edition of the morning paper, and was back on the scene the next morning.

The world had changed.

The old Ford dealership had been transformed into an emergency headquarters. Searchers from up and down the East Coast began pouring in, pitching tents, grabbing a bottle of water or cup of coffee, then heading out behind local residents to check hunting paths, trails, and logging roads. Donna and the family waited under the awning that had once protected shining F-150s, Mustangs and Fairlanes. The Highway Patrol brought in a helicopter, and the television stations jockeyed for space with their RVs turned remote studios. Somewhere I have a photo my photographer took of a younger me, jeans tucked into boots, a knife on my hip, rolled sleeve showing bleeding scratches as I handwrite an update to be called in by phone. The photographer was a gorgeous, long-legged blonde who raised eyebrows as she ran across a field and jumped into my arms, excited that one of the crews had found what they thought was a trail.

Sadly, it wasn’t Buddy’s trail. Just as when someone found tracks they attributed to his dogs, and when someone else found a toy that was positively identified as his, there was nothing. A little boy had vanished into thin air.

People don’t vanish; someday, the children of God will, but this wasn’t a mass, Biblical rapture. Crystal Soles, Buddy Myers, Brittanee Drexall, Brian Robinson, Jaime Southgate, Jessica Lowery, Jennifer Huggins, Brandon McDonald, Timeka Pridgen, and Zebb Quinn didn’t just disappear.

People don’t just vanish, especially little kids who finally have a future, little kids with dogs and toys and families who love them.

But Buddy vanished.

I got entirely too close to the story of Buddy Myers’ disappearance. It’s a basic tenet of the new business that you have to remain objective, but I caught the same fever that everyone else did. This was our child. Even if you had no earthly idea who the Myers’ family was before Oct. 5, Buddy became your little boy.

Once you saw the hope that rose and fell in Donna’s face, or the cars that rolled up with an entire church homecoming’s worth of fried chicken, potato salad, pizza, pecan pie and prayer, or the pickups loaded with five-gallon cans of donated ATV fuel, hauling more than the law allowed and filling the sometimes still-hot tanks of the tired, briar-whipped crews – once you spent a few minutes in that community of strangers turned family, Buddy became your little boy, too.

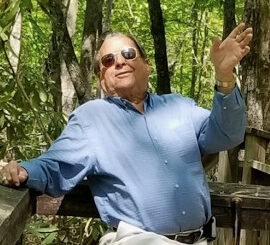

Buddy is just one of many children of all ages who are never forgotten by Monica Caison. I met Monica on the second or third day of the search. She was a loud-mouthed woman fussing at my lifelong friend, the chief deputy, a thirty-plus-year veteran cop. At first I wasn’t sure what kind of person I was dealing with – after all, she had the temerity to poke him in the chest with her finger – but it didn’t take long for me to realize that Monica was there for the family, as she was and is for every family when someone disappears.

She was the one who taught me that every missing person is somebody’s child.

The searchers scoured the swamps, the ponds, and the woods around Microwave Tower Road, but they never found Buddy. As the cold front blew in, bringing the promise of a great start to hunting season, the chief deputy called everyone, media and searchers alike, into what had been the garage at the Ford dealership.

The search was scaling back, he said. The weather was turning bad, and tornadoes were possible. He appreciated everyone’s work, and promised that the search would continue.

The next day was raw, bitter and blustery. I checked back by, not knowing what else to do. There were only a few searchers left.

The following Sunday, my mother went to the press conference at the Myers house, and was the first person to see Buddy’s dogs as they trotted into the yard, days after the boy had disappeared.

Buddy would be 26 now. He might have been a soldier, a trucker like his Uncle John, an athlete, a cowboy, a teacher. He might have been a law enforcement officer, a firefighter, or a medical student hoping to help people. Buddy might have been married and even a father by now, awaiting the start of hunting season, or scheduling work around youth league football practice, soccer and Dixie Youth Baseball.

But instead, he will always be a little kid who vanished on a lovely October day in the year 2000.

It didn’t take long for yellow ribbons to adorn doors and utility poles in the days after Buddy’s disappearance. They stayed there for years, fading and unravelling, threads lost to bird’s nests and breezes.

The yellow ribbons are gone now, as are many of the memories of those days in October, but for many of us, we will never forget when a bunch of strangers came together for a missing person who became everybody’s child.

Buddy’s disappearance is considered a cold but active case. If you have any information about Tristan Buddy Myers, contact the Sampson County Sheriff’s Office.