I happened to catch maybe two minutes of the Country Music Awards the other night. For reasons I cannot fathom, a bunch of the new stars were singing Phil Collins song.

I wasn’t even one of Phil’s songs that could easily cross the line into country, like I Wish It Would Rain, although remaking that song with anyone but Eric Clapton on the guitar would justify mindless violence. The song in question was one more associated with the TV show Miami Vice.

With all due respect to the performers with Little Big Town and Sugarland, two groups I think I may have heard of – Phil Collins’ Take Me Home ain’t country music, especially with a laser light show going on behind you.

I shouldn’t be surprised, I guess; country went city a long time ago, about the time the latest of these computer-synthesized singers were getting out of diapers.

There are some country music singers left—sadly, we recently lost the great patriot and singer Toby Keith, and a host of others of that last generation that influenced Keith, Trace Adkins, Allen Jackson and still more. What I find interesting is how those who dare to actually make music and perform without the benefit of technology are often the ones with the sharpest messages, and they immediately draw the fire of the politically correct crowd.

Aaron Lewis, for example, expressed the sentiments of so many folks with Am I the Only One? Lewis was pilloried in the media by people who immediately called him a bigot, a troglodyte and any number of other names. Turned out a courthouse in the video was allegedly the scene of a lynching during darker times — but that didn’t bother other, more acceptable performers who had used the same courthouse in their own videos.

I think country singers today have gotten scared of their own shadows. Where Johnny Cash married a black woman (that was before June Carter, and during segregation) the group Antebellum changed their name because the Greek term is one used to describe a style of architecture popular before the War Between the States, and often associated with plantations.

Think on that for a moment.

They weren’t Confederate Railroad (which didn’t change its name). Antebellum didn’t sing any songs about Southern pride (which does not glorify slavery). I don’t think they ever even hung a fake Confederate flag on their stage.

But because the word Antebellum might make somebody think something ill of them, they changed their name. I reckon the punk group Yellow Cab should have changed its name, since “yellow” was once a shameful racial slur sued against Japanese people.

Antebellum, by the way, means “before war”. It can mean any style that preceded any war, and in some foreign countries, it describes a different architectural style.

Toby Keith loved the United States of America; Allen Jackson still does. In those horrible weeks after 9/11, they both had songs that drew us together and strengthened us. The Angry American paired perfectly with Where Were You; tragedy brought us together, and once we had wiped away our tears, we went after the ones who attacked us, but we never forgot what was important – at least until the politicians endorsed by a billionaire former country singer turned internet influencing poptart came into power.

Country music once taught us to think; it told stories; it made us angry, helped us remember good times, and taught us that someone else had also experienced a broken heart or the loss of a loved one, or had fond memories of an old yellow car, a good horse or a loyal dog. Country song writers had highs and lows, just like normal people. They tuned their guitars to find something different, as opposed to tuning their computers to sound like everyone else.

Country lost its way and lost its soul somewhere along the time producers wanted to make music more marketable. It took no time at all for the plain sugarfree Jello to replace Grandma’s banana pudding. To be successful and appeal to the mass market, virtually every country song and by extension, every so-called country singer, had to produce the musical equivalent of the white or gray midsize SUV.

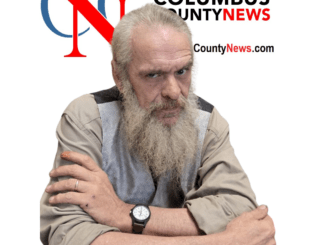

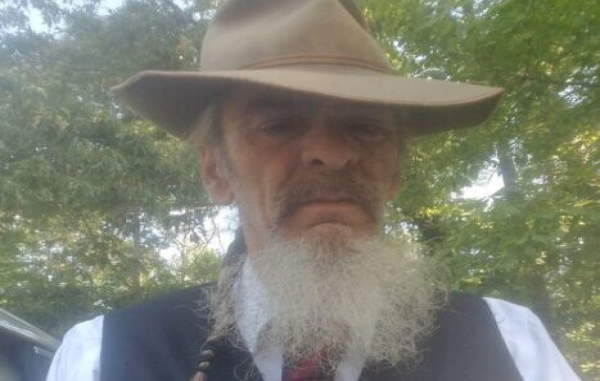

Look at how the country music industry responded to Christopher Anthony Lunsford, better known as Oliver Anthony.

He became known as the King of Homemade Hits with his song, Rich Men North of Richmond. Notably, he politely refused the advances of the big name recording industry types who approached him. Critics said that without the “help” of the professional pitchmen, he was doomed to failure.

Yet somehow, the YouTube release featuring his dogs wandering through the shot amassed five million views in three days, and made it to number one on the charts. While I don’t care for the cussin’ in his song, it has far more appeal than the latest remake of another reboot of a semi-forgotten pop song. I can relate to almost every word that he sings.

At the other end of the spectrum is Beyonce, another poptart (albeit, one with an incredible voice) who decided to get back to her ancestral roots and record a country album. It’s good to hear of folks remembering where they came from. She did a credible job with the songs I’ve heard – credible, but not incredible. Dolly Patron likes her, so she can’t be all bad. Her outfits are more reminiscent of a stripper in a country-western adult establishment than a country singer, but that’s not unusual these days, either.

I’m going to be the one to call out the elephant in the room here.

If she wasn’t black, I doubt her album would have created nearly the stir that it has enjoyed. Contrary to popular belief, there were black country singers before Beyonce (all the way back to the 1920s and 30s), and they didn’t have autotune or social media promoters. I wonder how many people were scared not fawn over her music – much less criticize it — because they were afraid of being called a bigot.

Commerce was having an impact on country music about the time I quit listening to country stations. That was after my beloved Miss Rhonda was the last DJ to sign off for WRRZ 880 AM Country. The homogenization wasn’t yet in full swing, but it was getting close, and the music no longer had the appeal that was still being mastered by George Strait and towards the end, performers like Clint Black and Garth Brooks (the latter of whom I never really cared for, although he is a talented singer and songwriter. If he just wasn’t so insufferably full of himself, and downright weird sometimes).

The term “country” was becoming synonymous with nothing more than drinking too much, maybe fighting a little, and then drinking some more whilst tearing up a field in a four-wheel-drive truck with a yelling scantily-clad girl beside a longhaired kid in need of a shave and a job. It had become, in a word, predictably boring. And it has gotten worse, for the most part.

Most of the storytelling has been gone for a while, based on what I hear blasting from the speakers of squatted trucks. The bards who shared the pains and joys of true first love, of loss, and of life have been replaced with male singers who forgot to get dressed and female singers whose outfits are comprised of dental floss and wishful thinking.

If this is the new way for country music, and people like it, I am happy that it makes them happy. I can easily turn the radio dial or even just hold a button and tell the music server on my cellphone what I want to hear, and I don’t have to hear about tiny cutoff jean shorts and throwing beer cans at mailboxes.

I am saddened, however, that the new breed of country singers has to rely on the pop music of their parents’ years to appeal to their market.

The late George Jones put it perfectly in his song, Who’s Gonna Fill Their Shoes?, to wit –

Who’s gonna fill their shoes?Who’s gonna stand that tall?Who’s gonna play the OpryAnd the Wabash cannonball?Who’s gonna give their heart and soulTo get to me and you?Lord, I wonder who’s gonna fill their shoes….

Indeed, I wonder.

Because whatever it is those people are performing, that ain’t country.

-30-