Twelve law enforcement officers from Columbus County will be honored at the sheriff’s office memorial park Friday as part of National Police Week and Peace Officer’s Memorial Day.

The earliest recorded death of a local LEO – the killing of Constable Jesse Simon Long – was never solved.

In the first decade of the 20th century, constables in North Carolina were somewhere between deputies and the elected sheriff in terms of power and responsibility. They had arrest powers, collected taxes, and served warrants, according to the state General Statutes. They were also responsible for generally keeping the peace, which was challenging during a tumultuous period of changing politics and racial discord in North Carolina.

Republicans and Populists joined forces in the state legislature, eventually taking the governor’s mansion from Democrats in 1896 for the first time since Reconstruction. Democrats responded by passing a new state constitution that (in part) was designed to disenfranchise black voters.

New state laws were also passed altering the operation of county governments as well as the responsibilities of elected sheriffs; in some cases those laws were undone by the next session of the legislature.

Sheriffs were the most powerful elected official in a county, and were responsible for creating their own budgets and salaries.

Some used the office to curry political favor by appointing salaried deputies and constables from powerful families, while others at least made an attempt to find qualified individuals for the jobs.

Jesse Simon Long is thought to have been one of the latter.

Long and his family lived in the Nakina area of Columbus County. He was the son of Simpronis and Sarah Elizabeth “Sallie” Faulk Long. His wife Jeanetta Caldonia Gore Long was the daughter of Joshua and Margaret Long Gore. Jesse and Jeanetta had five children.

When Simpronis Long died (the exact date is unknown), Jesse Long was a young child. His mother married John McDaniel Stephens in 1882. Stephens died in 1907, and as the eldest child, it’s likely that care and support for his mother fell on Jesse Long’s household.

The Longs farmed and had other business interests. The one-two punch of an extended drought followed by three hurricanes (including the possible Category Five storm of 1899), followed by the troubled financial times in the state and nation that extended well into the early 1900s likely helped guide Jesse Long into his law enforcement career.

Long was hired as a constable in 1905 by Alfred Smith “A.S.” Richardson, who was then serving as Columbus County Sheriff. Richardson was a familiar face in law enforcement and politics in Columbus, being the son of Sheriff Van Valentine Richardson.

Richardson served as sheriff in 1864-65, was reelected in the first election after the War Between the States, and served until 1873. A decade later he was elected again, then resigned to take a job as a U.S. Marshal on Christmas Eve, 1885.

County commissioners rented Marshal Richardson space in the county courthouse in 1886, and he worked closely with the sheriff and deputies on a number of cases. The move created the first documented existence of a cooperative agreement between local law and federal marshals in the county, much like the federal investigators assigned to the modern CCSO. A.S. Richardson naturally followed in his father’s footsteps.

While Richardson earned the tidy sum of $125 months on election to sheriff, constables were at the bottom end of the county law enforcement pay scale. They were paid anywhere from $1 to $5 for various tasks, and were expected to provide their own firearms, equipment, horses and transportation. County commissioners voted on whether to reimburse individual constables for their expenses.

If there was an emergency call in their community, constables were expected to respond, whether or not they got paid. Constables like Long had to house prisoners overnight if they did not have access to one of the spartan holding cells scattered across the county. There was no readily available jail cell in Bug Hill or Nakina, and travel on the dirt roads of the time was treacherous enough in daylight. Risking a ride to town on a wagon or one of the few automobiles along the rutted roads at night was asking for trouble, so constables and deputies in more remote areas regularly secured suspects until daylight made travel a little easier.

Sam Wilson was one of those suspects.

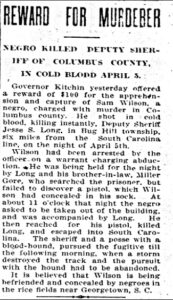

Wilson was arrested by Long on April 5, 1909, on a charge of “abduction,” according to contemporary news accounts. Little is known about Wilson, other than that he was black, and possibly an itinerant worker from South Carolina.

When he was a constable, Long lived approximately six miles from the state line in Bug Hill. As was common, Wilson was tied or handcuffed in a barn on the Long property, where Long and his brother-in-law Miller Gore, stood guard. Wilson was to be taken to the county jail the next day.

Around 11 p.m., the reports said, Wilson asked Long to take him outside so he could relieve himself. Long loosened Wilson’s bonds as a courtesy – unknowingly allowing Wilson to gain access to a “pistol…concealed in his sock.” He drew the pistol and shot Long in the yard of the family home.

Long died instantly, and Wilson fled. Traditional sources say Gore fired several shots at the fleeing prisoner, but there are no court documents or news accounts to prove or disprove that part of the story.

Gore immediately contacted Sheriff Richardson, who assembled a posse and began trailing Wilson. For a while they thought they had the suspect, since the posse had the assistance of a bloodhound that struck a hot trail.

They “pursued the fugitive till the following morning, when a storm destroyed the track and the pursuit with the hound had to be abandoned,” the Farmer and Mechanic newspaper of April 27, 1909 said.

The paper asserted that Wilson had escaped to the area around Georgetown, S.C., where he was “befriended and concealed by negroes in the rice fields.”

Long’s murder was not quickly forgotten. Gov. William Walton Kitchin offered a $100 reward for information about Wilson’s whereabouts. Richardson also continued following leads about the suspect, supposedly even after he left office for the last time in 1913.

Long was 38 years old when he became the county’s first known line of duty death. He is buried in the Joshua Gore Cemetery in Nakina, along with his wife and other family members.

The sheriff’s office will host its annual Peace Officer Memorial Service Friday at 11 a.m. at the sheriff’s office. Long will be among the fallen officers. Other line of duty deaths include Fair Bluff Police Chief Bradd Cribb; Deputy Hoke Smith; Trooper Harry T. Long; Deputy Milford Hardwick; Fair Bluff Patrolman Lennue Hammond; Wildlife Enforcement Officer Troy Simon; Deputy Bob Hinson; Charlotte Police Officer Andy Nobles; NCDMV Enforcement Officer Franklin Perritte; Tabor City patrolman Timothy “Shane” Miller; and Master Trooper Kevin Conner. Relatives of the fallen officers will place flowers on the county memorial to fallen officers.

The public is welcome.