Tuesday, April 25, 1978, was a beautiful spring day.

A new department store had opened in town, and a beauty queen cut the ribbon. It was an election year, so there were rallies, speeches and pig pickings everywhere. The leaders of a neighboring town were mulling a water and sewer project. A man had stabbed another one in a drunken fight, and in turn been hit with a baseball bat, but both were expected to recover and face charges.

Transfer trucks rumbled and rattled over the train tracks at Railroad Street and Cumberland Avenue. Trains shook dust, mold and plaster from the walls and ceiling of our newspaper office. For some reason, there weren’t as many afternoon beer drinkers at Charlie’s Tavern, so the jukebox was silent.

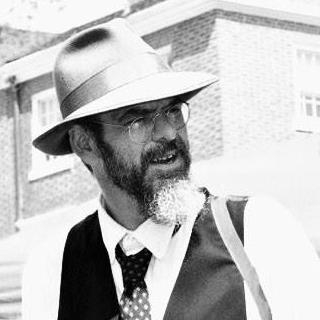

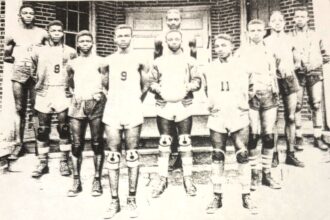

Like any other day, I expected to see my friends when I got to the Dispatch office. I don’t mean the other paperboys; we had a tenuous alliance against those who delivered the other newspaper, but that was all. I went to a different school and was a little younger, so we weren’t really close. My friends were those who worked with and employed my parent. Mr. Billy, one of the owners of the paper, whose wife was always so sweet to me. The pressman, who unwittingly taught us boys new and more creative ways to use forbidden words. The photographer, Tim, who was just cool. Mr. Johnny, the sports editor. Mr. Wade, who wrote a political column, covered meetings and was once punched by a state legislator.

I had other friends at the paper, too – the machines. The machines were the tools we used to create a paper five days a week. I say “We,” even though my role was insignificant at best. Truth be told, I was more pestilential than productive.

The machines were my friends; benevolent or dangerous, modern or antiquated, they didn’t call people names or make fun of them. The machines only did what they were told by the person operating them.

I loved the manual typewriters, and I still love the resounding “clack” of a key striking a piece of paper held on a platen, the key forcing ink into an impression of a letter that would become part of a word that would become part of a sentence, then a paragraph and a news story with the symbol — 30 — at the bottom. That symbol meant the end, the work was finished.

I loved the Associated Press ticker, where before anyone else we learned of the fall of Saigon, President Nixon’s resignation, the death of Elvis, and so many other events that shaped the world. A light above the ticker would flash when something important came across. The light backed up the bell, since another bell would be lost in the noise of the back shop, where the machines spat and roared and ground and gave birth to our newspaper.

It was hard to keep me away from the machines, although many of them were, truth be told, nightmarishly dangerous for a nosy little kid. One had taken a man’s hand back in the 1930s; another had seriously injured someone else a decade or two later.

We were unusual, in that our paper used both old lead type and modern typesetters. I loved the Ludlows and Linotypes that created words out of hot lead that spattered my father’s arms and created the dust that would someday kill him. Their reversed letters and words, locked in a chase, would be printed in the job shop, and the resultant headlines or graphics waxed down beside the tape created by the Compugraphic phototypesetters. I didn’t much care for the stinking, finicky Compugraphics. They frequently broke down, causing the paper to be late, which meant I was late getting across the railroad tracks to make my rounds, dropping ten, fifteen, 20 copies here and there at stores.

I loved the whole process of creating a photographic negative from a page, using a massive camera and lights that were so bright you saw spots for a half-hour if you didn’t cover your eyes. The negative would be processed, then used to burn an image onto a sheet of aluminum, just like a photograph. That sheet was then coated in chemicals, bent on the ends, and attached to the rollers on the press.

I loved the press, a massive Goss Community.

It smelled of ink and paper and heat and oil and power. It was a symbol of so many things that were important – history, truthfulness, and service to the people who paid a dime for a copy of its offspring every day.

There were dozens of moving parts, and a bell that would ring just before the motors began to hum and the units rolled, slowly at first, then faster as the pressman adjusted the ink for just the right flow. A conveyor belt spat out the copies of the paper, and on good days, a pestilential little kid might be allowed to clear huge armsful of the early copies that couldn’t be sold. One had to be fast, though, since the junk had to be cleared before the “good” copies came down the same conveyor belt.

Fewer papers had been printed that day; I didn’t fully understand why, even as I made my rounds and a couple of the vendors expressed sorrow and concern, as if someone had passed away. I knew things were going to be different. I just didn’t know how.

When I got back to the office that beautiful day, my friends were gone. Mr. Johnny left when the news came that we were being bought out and shut down. Mr. Billy did what he had to, then headed for his beach house to hide and heal. The pressman supposedly went on a legendary drunk. Mr. Wade only came in a couple times a week, so I didn’t expect him to be there. The lady who ran the front counter (and who often made my mother cry) had already quit. I think Tim the photographer, who had helped run the press, was around, but I don’t recall.

Something was wrong. I couldn’t figure out what, but something was wrong.

I didn’t immediately see my father, but I do remember speaking to my mama, then trotting back into the magical cavern where the dragon and all its kin lived. I was likely about halfway back when I realized what was wrong.

The entire building was silent.

The phototypesetters usually hissed and crackled at the end of the day. The Linotypes would usually still be warm to the touch; they made popping noises as they slowly cooled. The labeling and tying machines made a flat hammering noise, followed by the sound of the lever going down and the string whipping around each bundle of fresh newspapers, one, two, three times. It was still. The AP ticker was silent and unplugged.

On one of the layout tables, where the papers were put together, was a piece of letterhead with The Dunn Dispatch in letters at the top, and the handwritten symbol – 30 – in the middle of the page. That replaced our editorial cartoon that day. It worried me, but I still didn’t fully understand.

Then there was the press, the center of everything, usually surmounted by someone cleaning the rollers, maybe cursing at a balky part or removing the plates.

On that afternoon, there was nothing.

The press, the hungry, friendly dragon that fed us and protected freedom, the one that took words and pictures and put them together for eager readers to grab from their doorsteps, grocery store counters and clear-front boxes opened not with a magic word but with a dime – the press was silent.

Like the old lion Robert Ruark put out of its misery, our paper’s back had been broken, and it was tired of fighting. The hyenas were waiting patiently to eat it alive, but until that afternoon, it wasn’t ready to give up.

When the press went silent that afternoon, our paper ceased to exist, just as surely as if someone had mercifully shot it between the eyes. The roar of the press and the machines and the people was hushed forever.

I made my way back up front. I was too big to be scared of such things, but I was spooked, and I wanted my mother and daddy. My human friends were gone, and my friends that were still there – well, they were silent and dead.

In the silence of that old building that afternoon, I finally did hear a sound, and it chilled me to the bone.

Like most boys, my father was my hero, the man I wanted to be like when I was grown, the bravest, smartest man I knew. But he was making a sound I’d never heard.

In the silence of that old office, I heard him crying.

And for the first time I could remember, I was truly afraid.

For 21 years, the Old Man wrote a column every year, saying goodbye to The Dunn Dispatch. Sometimes it made print, sometimes it didn’t. In 2001, he lay in his hospital bed, too weak to sit up. He asked me to carry on his tradition. I promised I would, and for 20 years, I have kept my word. I kept my promise to my father.

I also made a promise to myself that day, about another column. Lord willing, you’ll read that one in a few days.