My father called my name, softly at first, then a little louder. The shadows outside my window were long, truncated by the sun rising on the opposite side, chasing away the night across a bed of frost and pecan leaves.

Papa knocked on the doorframe.

“You said you wanted to get up,” he said, just above a whisper. We didn’t want to wake Miss Lois, knowing how hard of a day she would have, making sure Thanksgiving was perfect.

I rolled out, and my dog Dudley hit the floor with a huff, as if to say he was wondering if I was going to lay abed all day. A half-hour later, he was happily galloping beside my bicycle down the street, heading out of town as fast as we could. I had overslept, but not too badly. The woods where we hunted were fairly forgiving, and I had kicked the knee-deep leaves away from the paths in my favorite oak grove the day before. My belly was warm, fueled with a ham biscuit and a single cup of coffee (heavily sugared and creamed) at the table with my dad.

Papa didn’t hunt, and would only reluctantly eat quail or doves. He always encouraged me, even driving an hour or more so I could deer hunt. He made sure I had good mentors, helped me get permission, and made darn sure I remembered what would happen if the game warden had to call him.

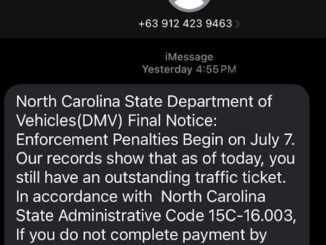

There was no game warden to worry about this morning. I had my license, of course, as well as the blessing of a couple landowners to plunder their fields and woods. Slung over one shoulder was an awkward military surplus shoulder bag, and distributed evenly in my coat pockets were a couple dozen shells. My shotgun was in its case, strapped to the frame of my bicycle.

I stashed my bike behind the brush pile, as always, and carefully crept to the edge of the pond; ducks occasionally visited there, mallards passing through en route between the cornfields and the two rivers. I’ve never really been a duck hunter, but I wouldn’t have passed up a shot, had one presented itself. We didn’t have steel shot rules back then, and I was only loaded with Number Sixes, but my eyes and instincts were significantly sharper.

There were no ducks — which was likely a good thing, since Dudley was the only retriever I’ve ever known who hated water, especially cold water. We made our way across a pine straw carpet to the edge of a dry cornfield, a few brown-gold stalks still stubbornly standing from the harvests of September. There were usually rabbits and a covey or two of quail in the brush guarding the ditch by the field.

Dudley was an unusual dog, one of those that comes along maybe once in a lifetime. He would retrieve a feather-shedding dove, and flush a quail with a certain lazy unprofessionalism. He would chase a rabbit, only occasionally barking as if he couldn’t understand why the rabbit was being so rude. He wasn’t a squirrel dog, but his curiosity often took him places that would cause a squirrel to carefully change sides of a tree — usually putting said squirrel in my sights. He had nothing good or bad to say about possums, but he hated coons. The only time he ever met a beaver, it badly confused him. All in all, he was a strange dog, a golden Labrador mix who hated water. Most importantly, he was a perfect companion.

We found no quail that morning, although as I recall I did knock down a brace of doves. They were the nervous, confused doves of the old “short season,” and it was purely God’s grace I got either of them as they flew past the boy in jeans and Army coat with a big yellow dog half-hidden in the broomsedge. The sky was mostly clear, half-covered by clouds of the kind that threaten snow (it was cold enough, but barely) yet rarely even bring rain during the Month of the Beaver Moon.

There was one out-of-range rabbit who, had he run any faster, would have left a twisted trail of fire across the field into the woods. We wished him well and promised to kick him out of his hiding place some other day.

Common knowledge said it was too late for squirrels, but when the ground grew too cold for sitting we followed the ditch to the grove where I had kicked free a path or two the day before. It was gloomy enough there that I’d shot bushy tails there in the middle of the day on occasion. As always, Dudley began exploring the wonderful scents on the ground as I tried to become part of a tree, the now-solidly risen sun behind me. I will never figure out how you can brush a spot in the woods clear of nuts and rocks, only to have twice as many appear and try to dig their way through your jeans and long handled underwear at the moment you least need to fidget.

The squirrels in that grove hadn’t read the rules about mid-morning, or else they were working overtime. After a few minutes they returned to their usual business, cussing at Dudley, who ignored their vulgarities like any superior gentleman walking through a bad part of town. Had I been carrying my .22, I likely could have hushed their fussing, but they were just barely out of shotgun range.

I called them, blowing kisses and scratching two dimes together, but my entreaties fell on deaf ears. Instead I just sat and watched as they ran circles around an oak that may have seen Sherman’s troops chasing Johnston’s Confederates across this farm, back when the farm was still a working farm, not dark woods. I tried stalking the squirrels, but all that accomplished was to drive them into the hollow of a gum, since the wind of the night before had undone most of my leaf-clearing efforts.

I finally whistled up Dudley, and we crossed a sad excuse for a barbed wire fence to a neighboring farm. We did bust up a covey of quail there, but they were faster than I was. We made our manners to the horses as Dudley gratefully lapped water from the pond.

The sun was high by then, and my Timex said it was pushing 11. Miss Lois wanted us home by noon, and then as now, I loved to eat. I especially loved my mother’s Thanksgiving cooking: the turkey, packed with homemade stuffing, potatoes mashed into soft submission, the special “angel biscuits” she carefully created by hand, rolled out on a cloth that I think she had used since before I was born. When you could eat no more, there were pumpkin, mincemeat and pecan pies, washed down with sweet tea and the cranberry-ginger ale I got to mix in a decanter that had served our family for a century and a half. Miss Lois always stressed over those holiday meals, sometimes to the point of tears, but her stress was that of an artist, and those meals were her masterpieces.

Dudley and I stopped long enough to share the Hershey bar that was half-melted in my bag, watching the bream in the shallows of the pond, then we headed for home. I stuck my head inside and said hello, then went to clean my birds and myself. Dudley flopped gratefully in front of the fireplace, not far from where Papa was napping over the newspaper.

When I put the birds in the freezer, leaving a pair of semi-grateful cats to dispose of the leftovers, Miss Lois urged me to hurry up. The smells of that bright, busy kitchen were incentive enough. As always, she called after me.

“Did you have fun?”

I had a pair of empty shells for Thanksgiving, an exhausted dog, and a morning I didn’t realize I would remember four decades later.

Fun doesn’t begin to describe it.