Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) has been confirmed in a herd of dairy cows in North Carolina.

HPAI has several strains, all of which are commonly referred to as Bird Flu. The virus is highly contagious among waterfowl and poultry, according to the N.C. Dept. of Agriculture. So far this year, HPAI has been confirmed in commercial turkey flocks in Duplin and Lenior counties. A previous outbreak led the state to cancel flock swaps and poultry shows for nearly a year.

While HPAI can pass to humans under some circumstances, the effects are mild and such transmissions are rare. Humans and other mammals can act as carriers for the illness. It is most commonly spread by migratory waterfowl.

“A lot of mammals can get HPAI,” said Aaron Blackmon, livestock agent with Columbus County Cooperative Extension. “Birds are most susceptible.”

HPAI as first detected in a dairy herd in New Mexico, then in Texas, Idaho and Ohio. A farmworker contracted HPAI on a dairy farm in Texas, the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture said, and was successfully treated. The affected herds are being monitored and quarantined.

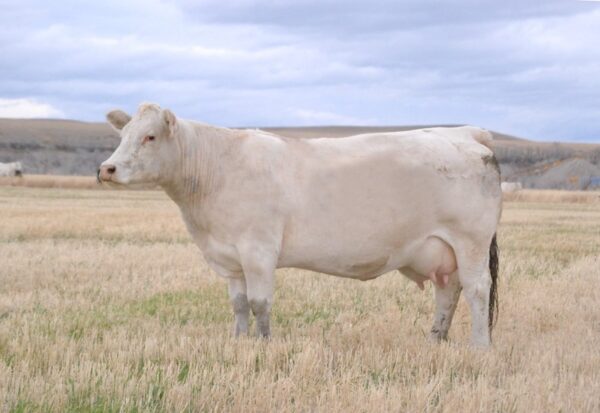

North Carolina has a small number of dairy farms compared to other states. The 2022 USDA Agriculture Census showed 100 total cattle farms in North Carolina, with 5,458 cattle. Only one operating dairy was listed in Columbus, and that farm had no milking cows at the time. Two were producing in Columbus in 2017, according to census records.

Nationally, there were 14,980 cattle farms, with 718,000 cattle on the 2022 census. Of those, 402 were bona fide dairy farms with 39,520 milk cows.

The virus does not affect milk, which is pasteurized and tested before sale. U.S. officials are concerned that a major outbreak among dairy cattle could have a negative effect on dairy prices across the country, however, if significant numbers of cattle are exposed to the virus and have to be destroyed. Beef cattle can be affected by HPAI, but the illness does not affect meat sold for consumption.

Columbus is not even in the top ten cattle farms,” Blackmon said. “We’re much more about the turkeys and hogs.”

Since HPAI can spread through any bovine, as well as swine and poultry, Blackmon said producers and backyard raisers should follow the same protocols as were in place during the previous HPIA outbreak.

“Try not to comingle the livestock and poultry water,” he said. “Keep your birds separated and locked up if you can, the prevent them being exposed to wild birds that may be carrying HPAI. There are always more migratory birds in the fall, and that’s when a lot of the exposure takes place.”

Blackmon said state and federal officials are monitoring the potential outbreak, but no major changes are expected in the near future.

“We have always known some mammals could carry HPAI,” he said. “Swine, cattle, and even some humans. You just need to be careful, and don’t take animals that appear sick.”

HPAI can produce listlessness, diarrhea and weakness in birds. IT can spread rapidly, but basic precautions can prevent humans carrying or catching the virus.

“At the minimum, don’t expose your birds to other people’s flocks, and practice the same biosecurity measures we’re all familiar with. At the very least, change your boots if you’re working around birds that might be exposed.”

Guidance from FDA on milk safety during HPAI outbreaks is available at this link – https://www.fda.gov/food/milk-guidance-documents-regulatory-information/questions-and-answers-regarding-milk-safety-during-highly-pathogenic-avian-influenza-hpai-outbreaks#:~:text=Because%20of%20the%20limited%20information,those%20infected%20with%20avian%20influenza.

NCDA&CS updates information on avian influenza on their website at this link- https://www.ncagr.gov/divisions/veterinary/AvianInfluenza.